It’s a fact of history that it is not always the person that first conceived something that is remembered so much as the person who made it famous. In ukiyo-e, this is particularly true of one of the nineteenth century’s most lasting and noticeable genres – the musha-e or warrior print.

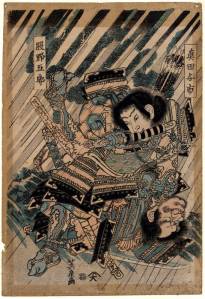

Toshidama Gallery is fortunate to have acquired a Kunisada warrior print from early in his career, Okabe Rokuyata Tadazumi in Combat with Satsuma no Kami Tadonori. This great and innovative piece is dated to 1820. What is remarkable about it is how closely it resembles the warrior prints that made Kuniyoshi famous and generated a cult of warrior tattoos that have remained popular until the present day; the more so since it predates Kuniyoshi’s greatest series of musha-e, The 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, by seven or eight years. I’d like to look at the context of the Kunisada print, what came before and what came after.

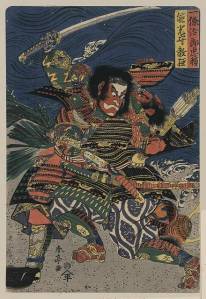

The first example is very similar to the Kunisada; the scene is from the same story and involves the same battle. In this case the artist is Katsukawa Shuntei, the scene being the fight between Ichijo Jiro Tadanori and Noritsune. The date of the piece is between 1810 and 1820 and clearly all of the essentials of the genre have been established: the intense detail of the armour, the high colour and most importantly the complex knot of physical contact, and the raised sword; the action stilled at the point of death, the figures not only filling the page but barely contained by its edge.

Moving forward just a few years we can see that in the early 1820’s Kunisada is relying on much of the tradition of Shuntei and Eisen (shown pictured above) for his rendering of the fight between Okabe Rokuyata Tadazumi and Satsuma no Kami Tadonori. Kunisada respects the horizon line – the horizontal division that breaks the flat scene into roughly one third to two thirds. The incidental details (such the drawing of the feet of the fighting warriors) are similar but Kunisada has added something else… the figures in the Kunisada print are larger than life… their eyes bulge, their heads are large and their expressions personalised; the physicality of the struggle has been greatly emphasised. The exaggerations lift the print out of the ordinary and turn it into something new – art perhaps.

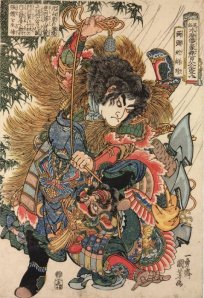

Looking at Kuniyoshi’s masterful series, The 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikodenfrom 1830, it’s easy to see how Kuniyoshi built further on the exaggerated themes that Kunisada (who was unknown and penniless at this time) had started to develop in 1820. In his portrait of Ryotoja Kaichin, Kuniyoshi chooses to place the two figures in the same spatial plane and at the same proportion to page size. Like Kunisada, the tangled forms of the physical contact of the two warriors is emphasised; the patterns and colouration here are similar also… but look at the expression of the defeated figure; the bulging eyes, the grimace, the knowing acceptance of imminent death. These two prints are so close that they could be by the same hand and from the same series. And yet – Kuniyoshi’s has more authority, it is less tentative, the gestures are more emphatic and the face of Kaichin is more naturalistic, more characterful. It was this series of prints that made Kuniyoshi famous, and to some extent expanded a genre of print into a national obsession (at least for a while).

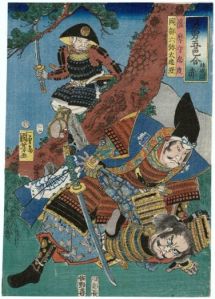

Kuniyoshi was to show his debt to Kunisada more explicitly as the print of the same subject (illustrated) from 1858 more than clearly demonstrates.

I sometimes think though that Kuniyoshi’s contribution to the musha-e is exaggerated. His prints are without doubt masterful and justly praised but we can see that their inception is based upon a growing development of a style that he so totally conquered that it ceased to innovate for the remaining century. It was not until the new naturalism of the late nineteenth century and the war with China that artists in Japan found new ways to show the warrior in action.

Pingback: Japanese Prints In Context: Kunisada Warriors (ukiyo-e) | Modern Tokyo Times