Chris Bucklow is one of Great Britain’s leading contemporary artists. He has work in the collections of the Guggenheim Museum New York, the V&A London, the Museum of Modern Art New York, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, among others. His work has developed from the early success of his sculptures in the 1990’s via a series of internationally acclaimed photographic projects which use pinhole technology on a grand scale. Over the last few years Chris has returned to painting, creating surprising and very successful paintings that betray an insistent personal narrative and communicate universal myths that clearly resonate with contemporary audiences. Chris is interviewed below by Toshidama Gallery director Alex Faulkner, where they discuss their shared enthusiasm for the mysterious world of Japanese woodblock prints. Christopher Bucklow has just exhibited new paintings at Riflemaker Gallery London.

Chris, you are showing some triptychs at Riflemaker Gallery… I know your interest in Japanese prints that use this format – is there a connection?

Well my subjects often seem to demand the same wide format that a Japanese triptych occupies. It’s something to do with a need for a narrative. But the paintings don’t start off as triptychs, they start as single panels which sometimes grow into triptychs when I add sections to the left and right. Usually this happens as I begin to get involved with the subject. At this point I begin to feel like the single painting I’m working on is a section of a time stream. So the bolt-ons are the ‘before’ and the ‘after’.

You could liken the way I work to a séance. I start by painting an empty space; a room or a landscape, and then I wait for the ‘knock’ as a figure wants to enter. As the painting progresses and I start to feel in contact with it, then I begin to know who the figure is and what its back story and future is. And so the painting grows wider to look like a triptych.

Time is not simple in these paintings. They don’t read left to right, or right to left as Japanese images do. Strangely enough, time seems to flow towards the centre, from the future and the past. It’s as if the ‘now’ is produced by the collision of influences from the past and the future. Obviously this is weird, but it feels right when I’m painting. I can’t explain it, but I’m sure a physicist who understands the full implications of the Double Slit Experiment might be able to come up with some theories about it.

With this bolt-on-as-necessary method, the paintings frequently become quite large, typically between 15 and 20 feet wide. Sometimes they only end up as diptychs, but sometimes they become polyptychs. I’m free to let it develop as it develops. Another great thing about this method is that it’s not so costly to transport them anywhere.

We were talking recently and you were interested in the maleness of some prints in the gallery…

Yes, the hero cycle interests me greatly, from any culture. Your own writing has done much to open this aspect of Japanese prints up for me.

The vast majority of the nineteenth century prints we were looking at in the gallery were theatrical… figures on a stage – acting out dramas… do you relate to that when you think about your own work – the dramas you create on canvas?

I certainly do. Over the years, through reading my work back to myself, I’ve become aware of what one might call the myth of my life. This content is a drama. Artists such as Kunisada were masters at translating theatre into ‘stills’ that bring the drama to life.

So many Japanese prints use archetypes in the telling of dramas – heroes, golden children, outcasts and so on. You are interested in this Jungian idea of archetypes so there is presumably some kind of resonance for you there?

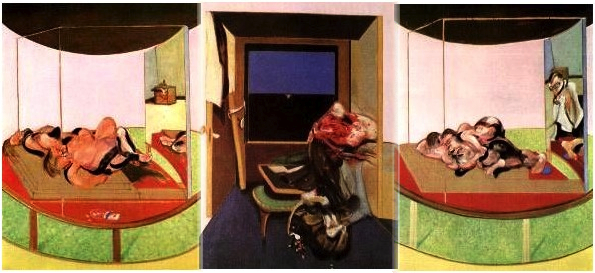

Yes, I can relate to that aspect of Japanese prints. But, when I actually look at a print it is a very, very long time before I can see anything else other than the design. In fact there are prints where I am never tempted to look beyond the design, because the design is so thrilling to my eye. Nearly all Japanese prints hold my attention visually in a way that is magnetic. I suppose it’s a commonplace idea to say that Japanese art is refined and nuanced. But that’s not how I experience it. Looking at the designs of Kunisada and Kuniyoshi, for example, I find the experience almost muscular, and quite visceral. My eye, my brain is kept involved, kept interested by the visual skills of the maker. It’s like the best music. Some composers are surprising and continually entertain through novel ideas and the bending of rules and conventions, others are pedestrian. The only Western artist who comes close to holding my eye’s attention in a similar way is Francis Bacon, but I’m certain he learnt most of his visual skills from Japan anyway. His triptychs are scaled-up oban format, one actor per panel, like a typical Japanese actor triptych, and one need only look at a work like his Triptych Inspired by T.S.Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes of 1967 to see that he’s been closely studying ukiyo-e. I would even go so far as to call his sex-scenes inspired by the Muybridge wrestlers, ‘Bacon’s shunga’.

Like Japanese theatre prints, there’s a sense of a shallow artificial space – an anywhere if you like – in many of your recent paintings. In the woodblock prints – and especially when the storyline of the play is unknown – there’s a sense of the individual figures being absorbed in a universal drama that is perplexing and at the same time recognisable. Is that something that resonates with you? Does it matter if the viewer is unaware that a figure in one of your paintings might be a portrait of Clement Greenberg or someone else?

I think that you would get an added pleasure from knowing who my characters are and what the forces are that they are personify, but that can only come if the picture is look-at-able and holds the eye as an aesthetic experience in the first place. I work in a way that is similar to Blake, in that I have invented, or rather discovered what my cosmic drama is, and my paintings participate in the unfolding understanding of it. But if I possibly can, I want to make images that hold the eye more than Blake’s images do. The Ukiyo-e masters are exemplars and standards to aspire to in this respect.

So many Japanese prints are narrative in form – and they had the luxury of playing with time and space on a single print. Contemporary painting currently eschews narrative and literary conventions but you seem to be defiantly swimming against the tide, so how important is storytelling to you?

Storytelling in the sense that Duchamp’s Large Glass tells a story is essential for me. Duchamp was a very literary artist, at one with the great tradition of classical allegory. There’s no real difference between the Large Glass and a Titian Apotheosis of the Virgin. It’s just that Duchamp wraps the whole thing up in new clothes, in his case, the workings of internal combustion engine etc. To me it’s a pity that he is so completely misread. The ready-mades are the most influential part of his work for our times, but really they are just pendants to the Large Glass. The Bride Stripped Bare is the central sun of his system, and the ready-mades are just orbiting planets. There is an alchemical element to the Bride, so one could see the urinal in this light too, as a vessel for collecting urine, one of the substances necessary to refine base matter into the Philosopher’s Stone. If you don’t know this then the ready-mades are just single fragments. This is exactly how they have been taken. And it has been a licence for all the fragmentary work that we see today. Here is an example… Damien Hirst. If the YBAs had understood the true literary nature of Duchamp then he’d have been making ‘joined-up’ work like this: A shark in a tank, ridden by a skeleton dangling the carrot of a butterfly on a stick in front of the shark’s face, while it swims through Charles Saatchi’s office on its way to heaven etc etc. Instead we get only those elements as individual fragmentary works: Shark, butterfly, skull, office. I liken it to mute pointing at things, rather than actual saying, actual speaking. Work like Hirst’s are words, or perhaps even only letters of the alphabet, they are not sentences, or paragraphs, let alone books, as Blake’s mode must be likened to. Though as I say all this, I am reminded of Damian’s paintings shown at the Wallace Collection a short while ago. There was great hope in me then that he was about to join all his work up, and SPEAK. Then we’d see all the work he is currently famous for merely as a preparation for speaking, a gathering together of his vocabulary. Funny that the curators of the Tate’s big retrospective left those paintings out! Potentially it’s his best work. Clearly they don’t see the point about Duchamp either!

Returning to the theatre… I’m struck how several of the recent paintings exhibit the nuts and bolts of painting – the artifice if you like. In ukiyo-e it was not uncommon to show the mechanics of the stage and there’s a visual link as well as the extra layer of meaning in the use of theatre flats and canvas stretchers.

Well, I do often paint paintings of paintings. All paintings are apertures for me, windows into the psyche of the artist. I like going through those doorways. The stage flats and screens in ukiyo-e are wonderfully hard to read – are they representations of landscape, or are they meant to be the actual landscape beyond? I’m after that kind of ambiguity. Not only is it real to my experience, but it’s visually involving for the brain to try to get a hold on. It’s a way to stave off boredom.

Something I notice in the prints and your paintings are different realities existing in the same piece. The portrait of Greenberg with the cutaway showing Berthe Morisot reminds me very much of the woodblock artist’s use of similar devices to show alternate states. Is this permeable reality important to how you think we perceive the world?

Well, it is in a way. The thing is that you have to realize all the people and places in my work are internal figures of the mind. They are like ghosts in a Renaissance memory theatre. It’s a world of representations in there. And they are layered and shifting, they are also in a non-Euclidean space; and there are mirrors of mirrors, some one-way, some two-way mirrors. The perspective is also axonometric, isometric and one-point at the same time. Another thing is that, while an energy might be represented by a person, another slightly shorter wavelength of that same energy might be represented by a different person. So the Clement Greenberg and the flayed Michelangelo in that painting called Brockengespenst, are the same person, the same energy, at different moments in its history, or time line. Oh, and in my cosmology/psychology, Berthe Morisot, and the flayed Michelangelo are double aspects of one entity.

It seems we are forgetting our own myths in the west and you seem to be busy creating new ones! There’s a sense of a personal mythos developing in these paintings – is it important to you to communicate this to others?

Blake said “Create a system or be enslaved by another mans.” I took him at his word and did just that. Though as my daughter has just reminded me, one can’t really create one’s system, you have to discover the one that you contain.

Japanese prints in the nineteenth century were characterised by strong colour and very bold imagery… they were popular and accessible – is that important to you as an artist in your own work… do you welcome the viewer inside, in a time when contemporary art is intent on being hermetic and exclusive?

Well I think you might have gathered from the above that my content is not terribly accessible. But I do like to see strong colour and to have my guts pulled around by a strong rhythmic composition. If my images are accessible visually it’s probably just a by-product of my desire to please myself: I am bored by John Cage and thrilled by Mahler, bored by rather a lot of rap, thrilled by The Mars Volta. Though I suspect we’d all like to be understood, deep down.

There are very clear anxieties about women in Japanese art – witches, demons and so on – but also strong women who are both revered and feared by men. There was a class of prostitute labelled a Castle Toppler, because of their ability to bring down great men. Women also seem to have this powerful role in your narratives and I’m wondering whether that is an aspect of you or something else entirely – Mandy Rice Davies for example appears in several works – a recent Castle Toppler?

Yes absolutely, Mandy Rice Davies is my Castle Toppler, and Clem Greenberg is her main target. But you have to remember that I am Mandy, just as I am Clem. They are both within me.

Kunichika and Kunisada: Two Men of the Kabuki Stage is showing at the Toshidama Gallery from 18th April until 23rd May 2014.

Pingback: Francis Bacon and Japanese Prints: The Arena of the Senses | Toshidama Japanese Prints

Pingback: Dimitri & Wenlop | Toshidama Japanese Prints

Pingback: Christopher Bucklow at Southapton City Art Gallery | Toshidama Japanese Prints