The subject of the Japanese (Chinese) zodiac would take many hundreds of pages accurately to describe. It is a complex system of Buddhist symbolism, planetary observation and Imperial obeisance.

The Japanese Zodiac and calendar were introduced from China in the sixth century. The Imperial court invited the priest Kudara to teach them how to draw up a calendar and with it the associated astronomical detail. In traditional Japanese culture, astronomy, astrology and the calendar are inextricably joined. This did not change significantly until 1876, after the modernisation of Japan and the establishment of the Meiji government. The subject is relevant to the study of Japanese prints for a variety of reasons. Dating of prints can be done through research into an artist’s work in reference libraries or more commonly by looking at the date seals which always appear on ukiyo prints right up until 1876. All ukiyo prints have a number of cartouches (small panels) littering the surface. These will be the title, the artist’s name, the series name, the artist’s seal and the censor seal and date. A combination of these cartouches enables us to date a print accurately, sometimes to the month.

Like the western system, the Japanese calendar (and zodiac) was divided into twelve parts; these twelve parts corresponded to twelve animals. The lunar months have 29 or 30 days which do not add up to a full year and hence one month is repeated every three years to keep in line with the seasons. The animals are the identifiers for each of these twelve months.

The animals of the zodiac were named by the Buddha as he lay dying. He promised all the animals that they would have a month named after them if they came to him to pay homage. Only twelve animals made the journey, namely: the rat, ox, tiger, hare (rabbit), dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog and boar. The ox led the procession with the rat riding on his back. As they approached the dying Buddha the rat leapt off the back of the ox to take its place at the head of the queue, gaining first place in the order of the months.

To confuse matters, the years are also named after these twelve creatures and by one of the elements of wood, fire, earth, metal and water, and in addition by one of two brother signs (older and younger). The twelve animals run in the order that the Buddha bestowed on them and the cycle repeats itself with the five elements and the two ‘brothers’ making a total of sixty-year, repeating cycles. Thus a year such as 1998 might be described as the elder brother of the earth tiger, and so on.

This complex system was deeply ingrained with symbolism and metaphor. Inevitably, by using such powerful images, the combinations of animals, elements and other astrological signs led to a hugely superstitious and symbolic system that dominated cultural life for centuries. Animals played a large part in identifying portents and events, hence their use in Japanese art. One might often see incongruous groupings of animals that appear to make no sense unless viewed through their relationship within the zodiac.

People in the west will on the main be unfamiliar with the complexities of the Japanese calendar although many people are aware of the zodiacal significance of the creatures. Here are some of the Japanese attributes of the various zodiac signs:

Rat:

The rat is a symbol of disease and dishonesty in the west, but is popular in Japan and considered a symbol of good fortune. Curiously though, the rat is most often seen in woodblock prints as the familiar of the evil magician Nikki Danjo.

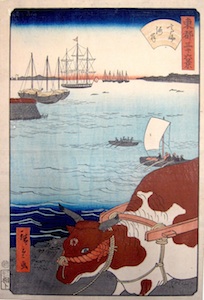

Ox:

Known as Ushi in Japanese, the ox is seen usually at the service of man – placid and tolerant and willing to serve (as in the illustration by Hiroshige II). It is sacred to the Buddhists because of its unswerving loyalty and is never shown in battle.

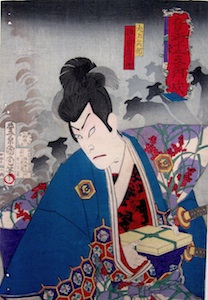

Tiger:

The tiger is a powerful symbol for the Japanese, most probably because of the long history of military conflict. For the early Chinese, the tiger was a fearful and supernatural beast but its supposed nature changed under Buddhist teaching and it became a symbol of strength, nobility and courage. In Japanese prints there is a strong tradition of depicting a tiger in bamboo. This image represents the strength of the tiger overcoming the thickets of sin and chaos and is highly symbolic. A famous print by Eisen on this subject (illustrated at the top) became the model for many Japanese prints like the Kunichika illustrated here.

Hare:

The Japanese do not distinguish between the hare and the rabbit. The moon and the rabbit are closely allied in folklore and appear together frequently, as inYoshitoshi’s Jade Rabbit and the Monkey from his famous 100 Aspects of the Moon series. In the west we refer to the ‘man in the moon’, so in Japan people make reference to the ‘hare in the moon’. The white hare or rabbit is considered sacred and killing it in the precincts of a temple is a great sin.

Dragon:

The dragon begins life in India before migrating to China and thence to Japan. It is a deeply symbolic and significant creature, standing for philosophy, transience, transformation and the cycle of life. It later became adopted as the symbol of the Japanese Royal household. Sometimes pictured as a legendary creature, it is more likely that one will see the dragon as the decorative motif on the kimono of a kabuki actor in printed form.

Snake:

Even before the arrival of Buddhism in the sixth century, the Japanese worshipped a snake deity called Orochi. The snake tends to be pictured in Japanese prints as the agent of revenge or of stealth. In netsuke, the snake is often shown wrapped around a skull – symbolic of souls reincarnating as serpents.

Horse:

Horses are mostly pictured in musha-e prints as the mounts for samurai warriors; this is reflected in Buddhism where it symbolises manhood. It is also seen as a phallic symbol and representative of fecundity.

Sheep:

The sheep is almost never depicted in Japanese art and if it does appear it resembles more goat than ram. This might be because neither animal is native to Japan – the sheep was not introduced until the modern era by the Dutch. Even then, Buddhist doctrine proscribed the eating of the meat and the wearing of woollen clothes.

Monkey:

The monkey is a popular subject in Japanese art although not so much in ukiyo-e. They are said to have magical qualities and offer protection against demons, and to have great longevity – often pictured holding the peach of eternity which they stole from the garden of the Queen Mother of the West. In woodblock prints they are most often shown as the companion of the folk hero Kintaro who it is said, was raised by the monkeys of the mountain.

Cock:

Associated with the sun – and hence the dawn – the cockerel is special to the Japanese and appears in a famous legend where it is brought to the cave of the Sun Goddess to coax her from her hiding place. It is this story that is most often used in Japanese prints. The bird can symbolise fearlessness in fighting and domestic bliss and contentment when pictured with a hen and chicks.

Dog:

Not associated with deities as such, the dog is rewarded nevertheless for being faithful and honest and appears regularly in mythology as a symbol of a good and trusting nature. In ukiyo-e it appears most commonly in the story of the Eight Dog Heroes (link). In this tale a princess is obliged to sleep with her father’s dog and gives birth to eight magical balls of light. Each of these becomes a man and they are the subject of stories of great heroism and courage, gathered together as a collection popularly called the ‘Hakkenden’.

Boar:

There are many Japanese folk stories associated with the boar. Highly regarded by samurai for its unflinching courage and reckless bravado, the boar was a popular challenge for hunting parties of samurai. In depicting a Japanese hero as being strong and courageous, ukiyo-e artists often resorted to showing the subject wrestling a wild boar with his bare hands – the qualities of the animal reflecting on the man.

With thanks to Guido Schiller for his research.

interesting

Pingback: The Japanese Zodiac – Animals in Ukiyo-e (Culture in Japan) | Modern Tokyo Times

Very informative!

I enjoy the bold use of color and lines in Japanese art. There is a good depiction of the essence of the animal almost as if they are characters. The animals are showing emotions such as anger and happiness almost as if they are human-like with their expressions. I like the way that the focus and the subjects are placed in the foreground of the paintings while the background has less emphasized detail you can still see it clearly.

Thanks for this article.

japanese wood-block prints